We may not be living out quite the dystopian nightmare that Margaret Atwood envisioned, but a new art exhibition has posted similar messages of solidarity in the most public places possible: on advertising billboards.

Called A LONE, the project was co-coordinated locally by nomadic gallery Vignettes, new poetry press Gramma and art space Mount Analogue, and funded by the Bill & Ruth True Foundation. In addition to the five billboards, there are wheat paste posters, audio recordings, stickers and a display of smaller work at Mount Analogue.

This “citywide exhibition of empathetic voices” is designed to address the lonely feelings that can arise in an urban environment — particularly one that is swiftly becoming unrecognizable to longtime residents. “It’s about living in a city and having those moments of solitude and isolation,” says Sierra Stinson of Vignettes. “There is a lot of stigma with loneliness, but it’s a very human experience.”

Stinson says A LONE (which is up through May) was inspired by the rapid and disorienting transformation of Seattle, and also by the essay collection The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone by Olivia Laing. “Loneliness is personal, and it is also political. Loneliness is collective; it is a city,” Laing writes. According to the organizers, A LONE is “meant to confirm that yes, you are alone, but we all are. We are in this lonely city together.”

The billboards are scattered across the city in high-traffic locations (find a map here). “We were thinking of commuters in Seattle, people waiting on a bridge, on Aurora, places you might be stuck in traffic,” Stinson says, explaining how locations were chosen. She hopes the signs reach the people who are engaging with the city and seeing it change on a daily basis.

“You’re not the only one” reads the billboard located at 15th Avenue Northwest and 70th Street in Ballard. It sits above a busy thoroughfare in transition, where dilapidated structures mingle with shiny new apartment buildings. The typeface is a simple serif, black on a white background. But something is a little off, a little blurry. It makes you blink your eyes and look again.

Portland artist Alyson Provax, who created the piece, explains that the phrase is printed three times, each slightly misaligned. “It serves to give the text a bit of visual anxiety,” she says. “I wanted the text to represent both certainty and shakiness.”

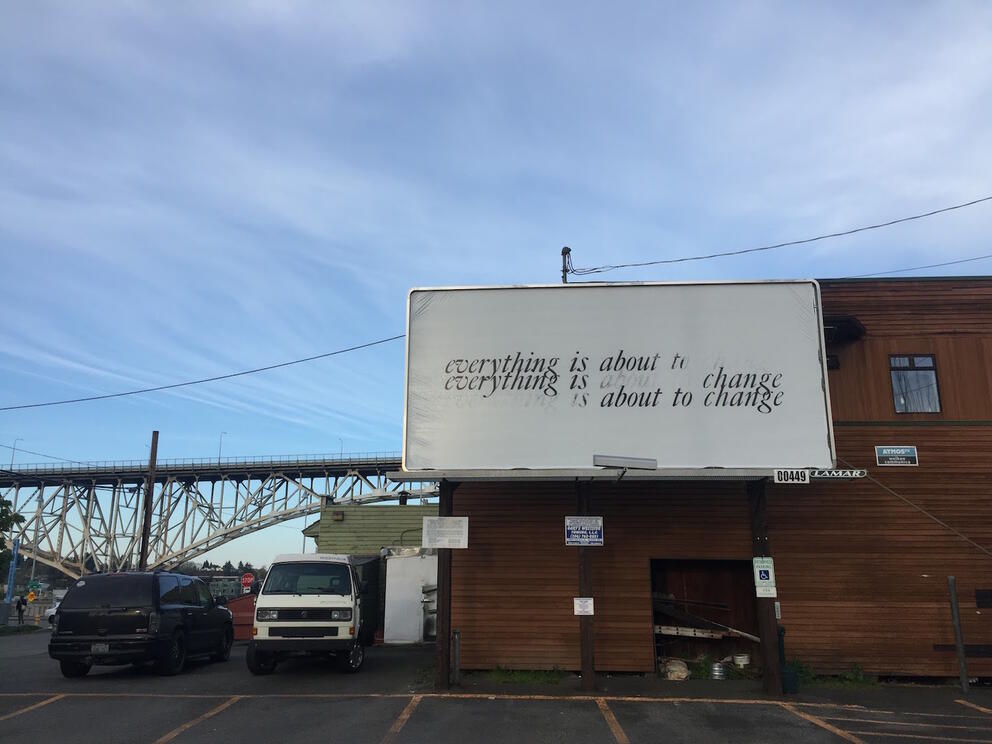

Provax has a second piece, located at the intersection of Nickerson and Florentia, near the Fremont Bridge. “Everything is about to change,” it reads. In the distance, the Aurora Bridge spans the Lake Washington Ship Canal, cut into the land in the 1900s. The phrase is printed three times, stacked in three lines. Some of the words fade out to a ghostly image. “The piece is only fully legible because of those multiple printings,” Provax says, “which shows an accumulation and a change over time.”

She says the message she wants to “advertise” with this billboard is that recognizing a state of flux can hold its own comfort. “Both Portland and Seattle are going through such powerful change,” she says. “It can be really disorienting. Parts of town look so different I feel lost, or like I’m in a dream.” But Provax believes that accepting the inevitability of change can help ease the anxiety about it.

Seattle artist and writer Laura Sullivan Cassidy’s billboard “Broken Languages” reaches out with a human voice. Placed in West Seattle’s concrete no-man’s-land where Fauntleroy Way intersects with several smaller streets including 38th Avenue SW, the sign features an abstract, color-saturated collage and the words “Call me: 206-483-CALL.” If you do, you’ll hear a sound collage of words and phrases and music. Cassidy posts a new recording every day. (She’ll post an archive of all of them starting June 3.)

“I keep calling to you in a broken language,” one says. “I keep hoping what you hear is a song… sing along.” Cassidy says she’s been getting feedback from people who tell her they really needed to hear it that particular day, or that the message gives them something to meditate on. “I think about it as something you do to start or end your day,” she says.

“Something that jolts you out of your reality and lets you reframe things.”

Also on view is a billboard by Seattle artist Leena Joshi, who comments on the changing city with a feminist, Guerilla Girls spin on the classic “Will the last person leaving Seattle — turn out the lights” billboard from 1971. In hers, an image of Mount Rainier looms behind an industrial landscape with the phrase, “Will the last bad ***** leaving Seattle — turn out the lights.” And Los Angeles-based artist Martine Syms contributes “Nite Life,” a huge fence banner surrounding the Capitol Hill light rail station. The words are taken from a Sam Cooke concert in 1963, when the singer was interacting with the audience. “IS EVERYONE DOING ALL RIGHT HOW YOU DOING OUT THERE...” it reads in part — a call and response writ large, at 580 feet long.

No matter the size, “Even a billboard can be invisible,” says Stinson, noting the tendency to visually tune them out. But her hope is that A LONE serves up surprise messages that sneak through to the people who need them most. “I like thinking about that moment of noticing — and connection.”

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.