Davenport — Fire!

We’d just been talking about it that morning. But it wasn’t really on our minds as we turned down on a long gravel drive off Highway 2 between Creston and Davenport. After three miles, photographer Matt Mills McKnight and I crossed under an old wooden ranch gateway with a cattle guard and arrived in the last century living in the present.

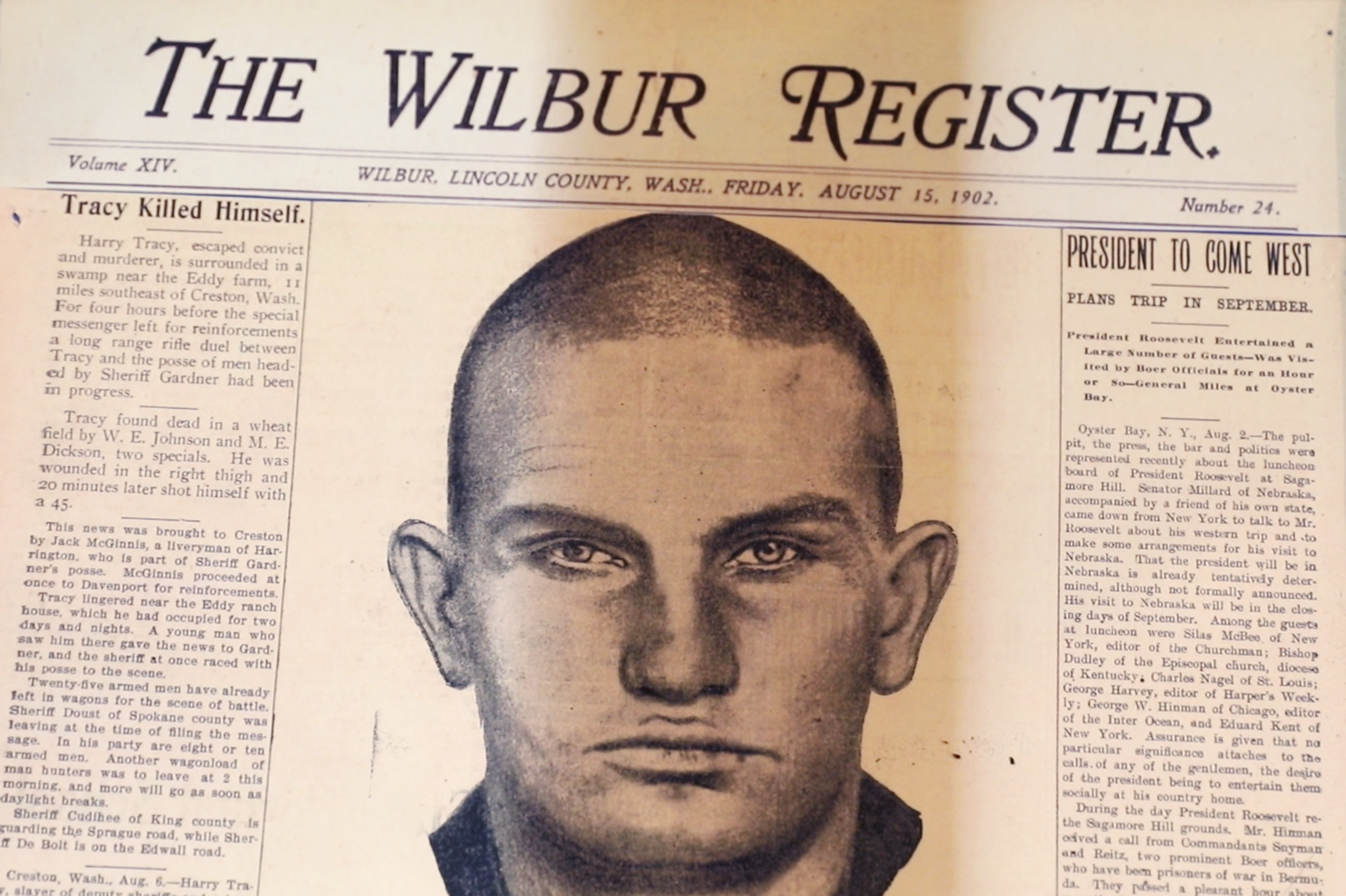

This was the Cole Ranch, run by cattleman Dave Hubbard. On this ranch, in 1902, one of the Northwest’s most notorious outlaws, Harry Tracy, had been hunted down by a local posse and died near a lump of basalt in a barley field maybe 100 yards from the barn. We wanted to see where this little bit of old West history was made.

After hearing the Tracy story and looking around the ranch, we got to talking with Hubbard about modern ranching. He grows hay and raises 800 head (400 cows, 400 calves) of Piedmontese natural beef cattle on 17,000 acres, much of it leased from the Bureau of Land Management. Hubbard is 56, lean and direct, with glasses, a mustache and a straw cowboy hat.

Dave Hubbard, a Piedmontese natural beef cattle rancher, exits the barn with his dog. This is the place where outlaw Harry Tracy once hid out and ultimately met his demise.

He lives with his wife in a house shaded by a grove of big trees that testify this ranch has been here for a long time. It’s a hot day, it’ll be in the 90s. Puffy white clouds are daubed on blue sky overhead.

Hubbard is smart, engaged with his industry, and he’s been around, having traveled to places like Africa and Mexico — trips that emphasized to him the importance of the productivity of American agriculture. He’s seen what starvation looks like. He sees himself as part of the small 2 percent of farm and ranch families who feed the rest of us.

“We’ve got to have people in government who understand agriculture,” he insists. We talked some about politics and Hubbard explained why he and other ranchers are hopeful about some of the new Trump administration’s appointees, though he passes on any on-the-record comments about Donald Trump himself.

Hubbard believes in some regulation — beef processing, he says is more hygienic and humane because of it — and he works with the BLM to manage his land to protect habitat for rare plants. But entities like the Environmental Protection Agency, he believes, often impose unfair and arbitrary rules that make life more difficult for farmers and ranchers without cause. “We’re not out here trying to ruin it,” he says of the land. “Extreme regulations hurt us even when we’re trying to do the right thing.”

This is an earnest argument you hear in Eastern Washington: people who insist they aren’t out to destroy the land, far from it. But they also get frustrated with rules and decisions that make a hard job harder. I felt some sympathy, as anyone who has had to fill out government paper work would. And while they feel demonized by environmentalists, it is also clear the guys like Hubbard are very attached to their land.

I was reminded how ag people, no matter how successful, always seem to feel on the brink. Bad weather, shifts in the commodities market, new rules and regs — these things undercut predictability, as does climate change. This year, for example Hubbard tells us that fire danger has increased because it was unusually wet. That’s counterintuitive, but true: The flora in the fields and pastures is double its usual height, meaning there’s a lot more vegetation that can dry and burn. This is exacerbated by government rules about the acres required to raise a cow and calf pair, which mean, he says, that the required acreage has more than doubled. According to Hubbard, it’s excessive and results in acres only half grazed, leaving even more burnable vegetation behind in the fields.

He tells us his ranch suffered a great deal from the 19,000-acre Swanson Lake fire of 2008 that swept across a large swath of his land. He lost some cattle. The cows crowded around the calves to protect them as the fire swept close, and some of those on the outside were burned and couldn’t be saved. Some cattle were so close to the flames their plastic ear tags melted and hung like cheese from a hot pizza.

He also lost some structures and fencing, and a lot of grazing land was reduced to ash. It came close to putting him under. “Fires in Lincoln County have increased dramatically,” he says.

After this conversation we left Hubbard’s ranch, but from the highway we saw some distant smoke. We wondered that that meant. We drove on to Davenport where the town of 1,700 people was holding its big annual festival, Pioneer Days. After lunch, we watched a horseshoe tossing competition, then went up to catch a belly flop contest. The announcer at the pool said the contest was postponed because all the contestants were off fighting a fire.

We quickly realized that the smoke we had seen was more than someone burning trash — and the smoke had seemed to be coming from the general direction of Hubbard’s ranch. We sped to the scene.

There were actually four fires, Davenport fire chief Craig Sweet told us. During the previous night, a lightning storm had swept the region. Two were near land Hubbard leases and had been smoldering since the wee hours. They can do that for hours before they flare up. So, while we were chatting with the rancher about fire dangers, the grass and sage nearby were quietly burning in remote fields and gullies not far from his place.

A sagebrush fire near Lake Creek in the Channeled Scablands, adjacent to Dave Hubbard’s federally-leased ranching property along Highway 2 in Eastern Washington.

Fighting fires here isn’t easy. These are the Channeled Scablands — wide open spaces marked by lava rock, wetlands and uneven terrain torn by ancient floods. Fires get into the roots of sagebrush and crop up in areas most fire trucks can’t reach, far from water and roads. Even locating the fire can be tough. We drove back to Hubbard’s area and followed billowing smoke via a gravel road miles into the countryside until we reached a road we couldn’t pass — our vehicle was too low to the ground and might have sparked another fire.

A deputy county sheriff pulled up trying to pinpoint the fire and access points that could be relayed to first responders. Some of the local departments have four-wheel drive wild land fire trucks and tankers to supply water. The deputy was a neighbor of Hubbard’s. A cowboy, neighbor Dusty Roller, pulled up hauling his horse after making sure cattle under his care were safe area, as long as the wind didn’t shift.

Everyone was sharing information while volunteer firefighters from nearby towns were trying to contain a blaze still miles distant from the nearest access point. They worked through the night, and got the fire under control.

It’s rare you have a conversation, and then have a point so dramatically demonstrated immediately after. Hubbard warned of fire risk and, voila! Ranching and farming are risky businesses. Fire is a major danger. Policies can have unexpected consequences that create new problems while trying to solve others. Weather can be unpredictable.

Another point Hubbard had made that morning: In the wake of the near-devastating 2008 fire, he had posted a notice at the local post office asking for volunteers for folks to come and help him rebuild for a day. Seventy-five people showed up on the appointed day, he says, and rebuilt buildings, cleared debris, replaced the fences. Hubbard lamented that the Spokane media, so quick to cover the fire, turned down invitations to cover the rebuilding by generous neighbors.

Farmers and ranchers live in country where people rely on each other to problem-solve, where the weather doesn’t just inconvenience you but can destroy your life’s work and living in a single flash. We saw proof of that one afternoon along Highway 2.

I called to check in with Hubbard a few days later. This time he was luckier, the fires we saw only singed the borders of his land. But he’d just picked up a weather warning: Another lighting storm was expected.

For more, follow #MossbackRoadtrip on Twitter and Instagram.