ASTANA, Kazakhstan - There comes a moment in traveling when you realize you’re not in Kansas anymore. On a recent trip to Kazakhstan, that moment came for me while visiting a pine-covered national park called Burabay in the northern part of the country.

At a small café set up for park visitors older Kazakh women lined up to buy a white drink in wooden bowls. It was kumis, the fermented mare’s milk that fueled the hordes of Gengis Khan whose descendants ruled this region and live there today.

I tried a bowl, which I can only describe as like carbonated skim milk seasoned with liquid smoke. It’s clearly an acquired taste. Imbibing it was a reminder that I was far from home where the staff of life for this formerly nomadic culture was the horse, whose milk and meat are still widely consumed as a beverage and even a pizza topping.

They do have Starbucks outlets in Kazakhstan’s capital, Astana, which is where my traveling companion Kenan Block and I were based. Maybe I should have checked for horse milk lattes on the menu. But the main reason for visiting the country was to explore Expo ’17, a three-month-long world’s fair, a first for this part of the world — and a draw for me, with a world’s fair obsession dating back to Seattle’s Century 21 Exposition in 1962. I have now attended 10 world’s fairs in 10 different countries.

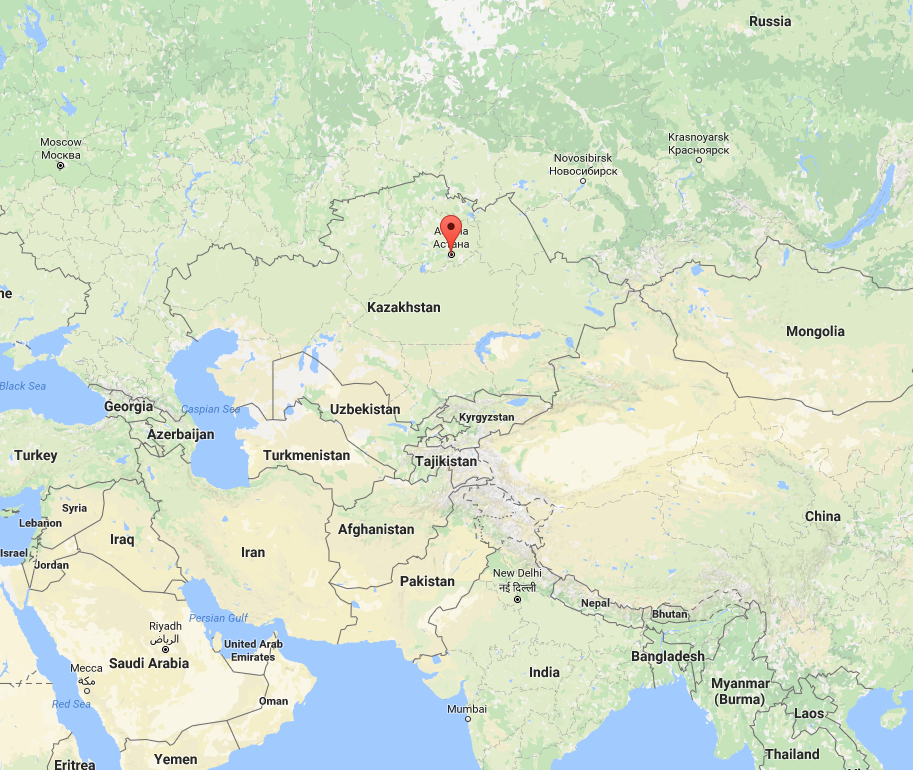

Kazakhstan is a former Soviet Republic, leans to the West and is considered one of the most progressive of “the Stans.” The main language spoken is Russian and it maintains close ties to that country. Kazakhstan has an oil-and-gas economy reminiscent of Texas or Alberta.

Astana is a new, planned capital city that emerged from almost nothing in the 1990s. Like Seattle, its skyline features a flock of cranes — Astana sprawls and rises, a government town with a population just over 800,000.

Built on flat terrain, not unlike Kansas, Astana is a surreal place chock-a-block with modern architectural landmarks. They have been throwing up large civic and private structures of all kinds, including government buildings, glassy skyscrapers, grand mosques, sports complexes, enormous upscale malls, pyramids, and towers including one featuring a giant golden globe on a tapered Space Needle-like base. The city resembles an Expo site with its imaginative structures, or a more ambitious Las Vegas without the gambling. At night, many of the buildings pulsate with colorful lightshows. The actual Expo seems almost redundant.

Kazakhstan is an Islamic country, but very secular and pro-business. The residents seem very middle class. A recurring theme--whether in the name of malls like the upscale Mega Silkway Mall adjacent to the Expo site or in major projects, such as the Kazakh government’s plan to expand rail links between China and Moscow, is the revival of the “Silk Road,” that ancient overland trade route between East and West of Marco Polo’s times. Rather than a remote former Soviet backwater, Kazakhstan envisions itself as in the middle of European and Asian commerce. One plan for the Expo site post-fair is to turn it into an international business complex.

Expos occur every few years, often in cities seeking recognition. Those who remember Seattle’s Century 21 Exposition in 1962 know the potential benefits of earning a place on the map.

The theme of Expo ’17 is “Future Energy,” fitting for a country that is a source of oil, gas and uranium for Europe, and also the timeliest topic in terms of climate change, renewable sources, and creating a more sustainable planet. The theme is vague enough that exhibitors can address it specifically, tangentially, or not at all. Judging from various pavilions, the future of energy is either more oil (Venezuela), building floating nuclear power plants in the Arctic (Russia) or trying to wean oneself off both oil and nukes (Japan). Over 100 countries participated and it’s fair to say that most of them are actively wrestling with climate change.

The centerpiece of the fair is an 8-story semi-transparent sphere called the Nur Alem that serves at Kazakhstan’s national pavilion and said to be the world’s largest spherical structure. It is filled with exhibits and multi-media entertainments that instruct about science, the solar system and energy renewables, like biomass innovations. It’s dramatic interior includes glassed-in elevators and a glass-floored walkway where visitors can look many stories down into the dizzying depths of the structure. This is not the Kazakhstan of nomads and yurts but of people embracing science and technology and looking at a future in space.

A young woman in the Nur Alem put on a Bill Nye-type science demonstration for the crowds that taught fairgoers about turning algae into fuel and the energy-producing benefits of bacteria. Women seem to have a strong voice in society here.

The country wants to be the world’s 30th largest economy, so says the longtime president Nursultan Nazarbayev. To be taken seriously, they need to make people forget — Americans anyway — the ridiculous image promulgated by the satirical “Borat” (full name: “Borat: Make Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan.”) The tech-embracing, business-friendly, modern Astana is a rebuke to that image, but it will take some work. We saw few Westerners at the fair, hardly any Americans. Locals seemed surprised to meet people from the USA and were almost disbelieving that we came all that way to just to see their Expo.

The main American presence at the fair is the USA Pavilion, staffed largely by an impressive cadre of student volunteers — multi-lingual college students working for room and board to represent their country. In Astana, however, I’m afraid their country has let them down. Did the USA pavilion address climate change, carbon pollution, or American innovations in solar, geothermal, or wind energy? Nope. The US simply declared with great banality, that “Energy is people,” and used a multimedia show with some digital millennial dancers to flash portraits of happy Americans you might find in any corporate annual report.

Our American pavilions at recent Expos have tended to disappoint in part because the U.S. government can’t spend money on them. Instead, they must contract with outside nonprofit groups that have to raise money from corporate sponsors, in this case companies like Chevron and General Electric. Initiated under the Obama administration and finalized during the early Trump era, the pavilion seems to have opted for a message that wouldn’t get anyone in trouble. Some of the students who manned the pavilion told us they thought the pavilion had been “sanitized.”

Wisdom sprouted in some unlikely places. For example, one of the best descriptions of the dangers of carbon in the atmosphere was in the Shell Oil Pavilion where visitors could don virtual reality goggles for a demonstration pitching the concept of carbon sequestration. Whether or not you think that’s a good idea, it was notable that the program accepted that carbon polluting greenhouse gases were a reality to be reckoned with, not a hoax.

The Vatican Pavilion included a film narrated in what sounded like the voice of a priest telling the story of creation: the Big Bang. That story fits both science and the Catholic belief in a single moment when God created the cosmos. It was a film worthy of astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson as it pitched a more accurate view of the universe than the Creationist view widely believed in the U.S.. Who knew that the church which persecuted Galileo would be a source of enlightenment in the age of Trump?

Small countries also impressed with creative discussions of their commitment to saving the planet. One example is Monaco, whose pavilion featured a beautiful presentation of that tiny country’s connection to the sea using video and shimmering mirrors. They also detailed plans for a new offshore “eco district” over the water to be completed in 2025, and they highlighted foundation grants they have been sending to Third World countries to help with environmental projects. In the pavilion the principality’s ruler Albert II is quoted as saying, “You don’t have to be a big country to have big dreams.” That in contrast to the USA Pavilion which appears to promote living in a dreamless stupor.

Kazakhstan is no Monaco—it is the largest landlocked nation in the world—but it too dreams big. While expositions were conceived in the mid-19th century as vast showcases of colonial empire, they have now become ladders for strivers, a place where economic Davids seek to be taken seriously as someday Goliaths, though perhaps a more benevolent version in the larger global community.

The path forward is technology, trade, and innovation. And consensus: since Spokane’s Expo ’74, a common theme at world’s fairs has been protecting the planet’s environment. Global warming is accepted reality the world over, the USA being a notable outlier. The question almost everyone else is trying to answer: how do we survive it?

The best Expos lay down a vision of what the future might hold. There was no single visionary message coming from Expo 17, except one: that a nation like Kazakhstan does not intend to be left behind. I doubt they’ll be able to convince the rest of the world to consume mare’s milk, but we can start to take their ambitions seriously.

Astana’s grand walkways feature sculptures and views of the city’s landmark architecture.