This mix of small-town charm and healing nature has attracted many new residents, some of whom have decided to make Cle Elum home full-time and others who use it as a part-time base camp for their adventures east of the Cascades.

In the past year, some residents ended up at Ederra, a master-plan housing community in a woody area behind downtown Cle Elum. The development promises the opportunity to tap into one’s “city dweller” and “rugged individual” sides with easy access to trails and to retail boutiques and restaurants downtown. When finished, Ederra aims to provide nearly 1,000 new homes on more than 350 acres.

This development has been at the center of a yearslong dispute over a 2011 development agreement between the city of Cle Elum and City Heights Holdings LLC, a business entity for Issaquah-based developer Sean Northrop.

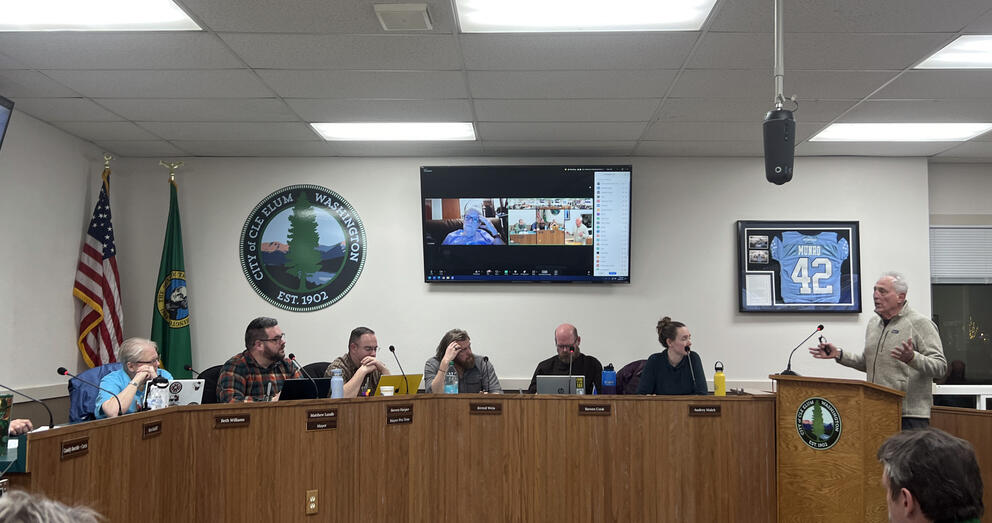

This battle came to a head late last month when the Cle Elum City Council voted 5-2 to move forward with bankruptcy. The vote came several months after a November arbitrator ruling that stated the city breached the 2011 development agreement and owed City Heights Holdings LLC $22 million in damages.

It’s a breakdown in a public/private relationship that dates back more than two decades, when Cle Elum was trying to figure out its future after the exit of several core industries, including timber and mining.

Like many other cities and counties, Cle Elum and Kittitas County have turned to such development agreements as developers expressed interest in bringing new projects to the region. Such agreements allow the city to have more control over development in return for concessions that allow the developer some certainty.

But more than a decade after signing a development agreement, councilmembers from the City of Cle Elum believe they’re at such an impasse with City Heights Holdings that they believe municipal bankruptcy — something that hasn’t occurred in any town in this state since 1991 — is the most viable option.

Before the Cle Elum City Council bankruptcy vote during its meeting on Jan. 28, councilmember Ken Ratliff gave an impassioned speech on how he felt the developer harmed the city, noting the city was financially stable before being handed the $22 million judgment in November.

“In my observation, the entire basis [of] this problem comes from an underfunded and undercapitalized developer who doesn’t have the capital to accomplish the work required,” he said.

Northrop maintains that he was open to discussing options for the city to settle outside of the $22 million judgment, including providing several in-kind, non-cash items such as issuing building permits free of charge for homes in the development. He maintains that the city has refused to engage in meaningful discussion.

“We’ve received a brick wall to all these efforts,” he said.

Having a say

Development agreements are voluntary contracts between a city and a property owner, and aren’t required for developments like these. But they provide both parties an opportunity to hash out several aspects of the planning process in advance, including determining allowable uses and structures, holding public hearings on the development and completing an environmental review.

Such agreements have been used on projects of various sizes, from a local shopping center to, in this case, a large-scale planned home community.

By the late 1990s/early 2000s, core economic engines — timber and mining — had disappeared from Cle Elum and the Upper Kittitas County area. This left the town with vast swaths of vacant property picked up by developers and investors.

Gary Berndt, mayor of Cle Elum from 1989 to 2004, observed all this real estate activity firsthand.

Berndt said he and others in the city and county wanted to avoid piecemeal development on property in and near the city limits and felt it was best to work with developers rather than against them.

“You’ll be subject to whatever they want to do,” Berndt said, noting the result if the city did not work with developers.

He also observed Kittitas County negotiate a development agreement with the then-owners of Suncadia Resort, built on thousands of acres of former timberland — a process that took several years before being signed in 2000.

Soon Berndt would undergo a negotiation of his own — Suncadia also owned hundreds of acres next to the resort designed for housing. The development agreement with Cle Elum was signed in 2002.

Berndt said negotiations for a development agreement can be tense. He remembers developers and their lawyers accusing him of negotiating in bad faith, and says he often annoyed developers by asking about numerous scenarios that could create legal liability. But he believed such tense conversations were necessary to ensure neither side was on the wrong side of a lopsided agreement.

“It ultimately comes down to the relationship — the ability to call each other, call each other out, cool off and come back to the table,” he said.

Annexation paved the way for the relationship

Northrop started his development company, Trailside Homes, in 1993, making a career of crafting large-scale planned communities that filled a need in each market he entered. He worked primarily in the Puget Sound area before moving into Kittitas County in the early 2000s, purchasing tens of thousands of acres of former timberland for a variety of residential developments, including the acreage that would become Ederra.

Berndt says that on the heels of the Suncadia agreement he was keeping his eye out for prospects for further development. The property for the Ederra development was not within city limits, so Berndt and others from the city council approached Northrop about annexing the property and working on a development agreement. Northrop initially declined, and Berndt stepped down as mayor in 2004.

In 2008, a few years after talking with Berndt, Northrop agreed to negotiate a development agreement with the city. Northrop said he pursued the deal — and the annexation — after city officials promised, among several things, a streamlined permitting process and a willingness to complete several aspects of the planning process up front, including public hearings and an environmental review. He also agreed to $10 million in various mitigations, including public safety and education funds.

After three years of public hearings and negotiations, the two parties signed a 25-year development agreement in 2011.

Former mayor Charlie Glondo, who signed the agreement, did not return a phone call seeking comment.

By the time Northrop approached the city about seeking subdivision permits in late 2019, eight years had passed. Most of the Cle Elum city council had not been around when the agreement was signed.

Northrop said he waited until the optimal window for developing new homes. By late 2019, Suncadia had been built out. The city attracted new residents from Western Washington seeking a reprieve from the bustle of the city and its growing affordability issues. Interest rates were also low, making it a good time to secure loans.

Northrop anticipated a relatively quick administrative review by the city’s planning department based on the 2011 development agreement. But city planning officials insisted he go through a complete planning process, including a public hearing and environmental review.

Northrop said city officials refused to abide by the 45-day administrative review period outlined in the agreement, insisting modifications were necessary. With the city refusing to comply, the developer turned to arbitration. In November 2020, the arbitrator sided with the developer, stating that the city had to follow the agreement.

Northrop went through the permitting process for the first two phases of the development to illustrate the delay created by city officials by not following the development agreement. According to Northrop’s calculations, as of 2023 the first phase of the development had been delayed more than two years, and the second phase was more than 18 months behind schedule.

Northrop secured permits for the first phase, and construction started in 2023. By then, Northrop claimed the optimal window to build had passed — raw material costs were rising, and borrowing money needed for the development cost more due to higher interest rates.

Cle Elum Mayor Matthew Lundh maintains that the city planning officials believed the development still had to go through some public comment process. Lundh became mayor in 2024, but was the city’s planning commissioner in 2018-2019 and served on the city council from 2020 to 2023.

The arbitrator, retired Judge Paris Kallas, would again side with the developer in two subsequent arbitrations, one in April 2022 and one last November, when she determined roughly $22 million in damages stemming from the city’s delays in the permitting process.

While crafting a development agreement is voluntary, the contract is legally binding, said Leonard Bauer, a planning consultant for the Municipal Research & Service Center, or MRSC, a statewide organization that guides local municipalities. Generally, only a few exceptions allow for modification — namely, a change needed to address a public safety issue.

Cities and developers should devote significant time to deciding how to resolve conflict, Bauer said. Given the terms of an agreement are often 10 to 15 years long — or even longer — the parties involved with the development of property could change, be it a new city council or a new property owner. Regardless, the development agreement and its contents are binding to the property.

For the city, bankruptcy is the best option with ‘no good choices’

Since the November arbitrator ruling, City Heights Holdings and the city have spent several months in conversations to reach a settlement that would be an alternative to the city paying the $22 million judgment.

Both sides have pointed fingers, accusing each other of an unwillingness to mediate.

Lundh maintains that Northrop and the city have been far apart on core facts, including the city’s options to avoid financial insolvency. Northrop and his attorneys have claimed in various statements and correspondence that the city has not been transparent about available funding sources to pay for the judgment award. Lundh states that is not true.

The $22 million judgment is more than five times greater than the city’s general fund — $4.5 to $5.5 million — which is where any money to pay the developer would come from, Lundh said. “It far exceeds our ability to pay.”

Any additional funding, Lundh said, would have to come from new or increased taxes on residents.

Lundh said Northrop had burdened mediation with an up-front cash payment, which, if the mediation fails, would leave the city without any money to proceed with other options, including bankruptcy.

Northrop maintains the city is trying to get out of making payments toward the judgment without showing that it is willing to sit down and do the work on a settlement agreement.

In December the city proposed a $4 million offer in which it would pay an initial $250,000 and then $250,000 annually over 15 years. Lundh said this was the most the city could come up with based on its existing budget and taxing abilities — $200,000 of the initial $250,000 payment would be generated by a utility tax increase.

Northrop said he declined the offer because it did not sufficiently show the city was serious about coming up with a satisfactory settlement in place of the $22 million cash award for their unwillingness to follow the development agreement. “What happens in year 16? They pay zero [dollars].”

Northrop proposed another deal, sent to councilmember Steven Harper minutes before the Jan. 28 city council meeting, offering to delay collections for 60 days if the city agreed to issue final approval of a subdivision permit for the second phase of the development by mid-February; issue 18 building permits at no cost; and waive $400,000 owed by the development for road improvements. The city would also make a one-time cash payment of $287,000.

During its meeting, the city council declined to consider the offer, with several criticizing Northrop for his refusal to acknowledge the city’s financial position and the impossibility of paying the $22 million award.

City councilmembers argue that it is not ideal to further tax residents to cover such a massive payout to developers, as taxpayers are already facing increasing costs due to inflation.

“For direct negotiations to be viable, at minimum, two things must be present: agreement on a basic set of facts and a willingness to compromise,” said councilmember Steven Cook, who called bankruptcy the best with 'no good options.’ “Unfortunately, in my view … City Heights Holdings have not shown either.”

Councilmembers Cook and Ratliff, in their comments, both painted Northrop and City Heights Holdings as looking to pillage the city and turn it into a company town for the development.

“I can only liken this bad dream to George Bailey’s bad dream — where his beloved Bedford Falls becomes ‘Potterville,’ a community that becomes unrecognizable from Bedford Falls,” Ratliff said, referring to the film It’s a Wonderful Life in which a developer turns a town into a slum after bankrupting its residents. “I do not want Cle Elum to become a ‘Potterville’ or equivalent in any shape or form.”

What’s next

Northrop said that contrary to the city council’s belief, he does not want the city to be financially insolvent. But he feels the city is attempting government overreach — both by not honoring the development agreement and by trying to use bankruptcy to pay less of the financial damages they caused by not complying with the contract.

Northrop believes that other developers and business owners should be concerned about the city’s response, noting that others can’t afford to spend millions in legal costs. “How about the espresso stand [owner] that doesn’t get fair treatment or a building permit?”

Northrop said he’ll continue working on the development and complete the first phase of homes, but it’s unclear how and when he could proceed with future phases of the development.

In the meantime, Lundh’s priority is to proceed with the bankruptcy process in the hope that a bankruptcy mediator can help settle the dispute, bringing the settlement down to a manageable dollar amount and minimizing the impact on the essential services the city must provide to its residents.

Lundh said there are lessons the city can take away from the dispute, including avoiding binding arbitration as the sole and final means of conflict resolution when crafting future development agreements.

“Essentially, you get in front of one arbitrator; they’re the judge and jury, and there’s no appeal,” he said, noting that even if the city disagreed with the $22 million judgment award to City Heights Holdings, there were no means through which to dispute it.

Bauer, the MRSC planning consultant, said that while development agreements can offer advantages, cities and property owners can proceed with a traditional planning and permitting process rather than be tied up in a contract lasting 10, 15, or even 25 years.

In addition, many small cities often do not have sufficient legal counsel to check on every aspect of a development agreement, a legally binding document once both parties sign.

“In the excitement of having a big developer looking to come in, it’s sometimes hard for the [city] staff or elected officials at the time to make sure they’re thinking of all the possible things that might happen,” Bauer said.

Bauer said a successful negotiation process requires both sides to acknowledge the other side’s needs. “In this case, it’s so broken; they’re not doing that, and they’re not believing each other,” he said. “It’s hard at this point to establish the trust that is needed in that relationship.”